The Book

Yearning for analog friendships, reading childhood writing, realizing we’ve been the same all along 😭

I don’t remember much about fifth grade besides the anticipation of change the next year promised. Older siblings and adults loved reminding us about our impending transition to middle school. Come September, they warned, we would have lockers and home rooms and there would be mean boys who would pull on our bra straps if we weren’t careful about concealing them. As if the regular anxieties I felt about my first major academic and social transition weren’t enough! In retrospect, though, the significance of all of this shrinks when I think about another development that year: the creation of The Book.

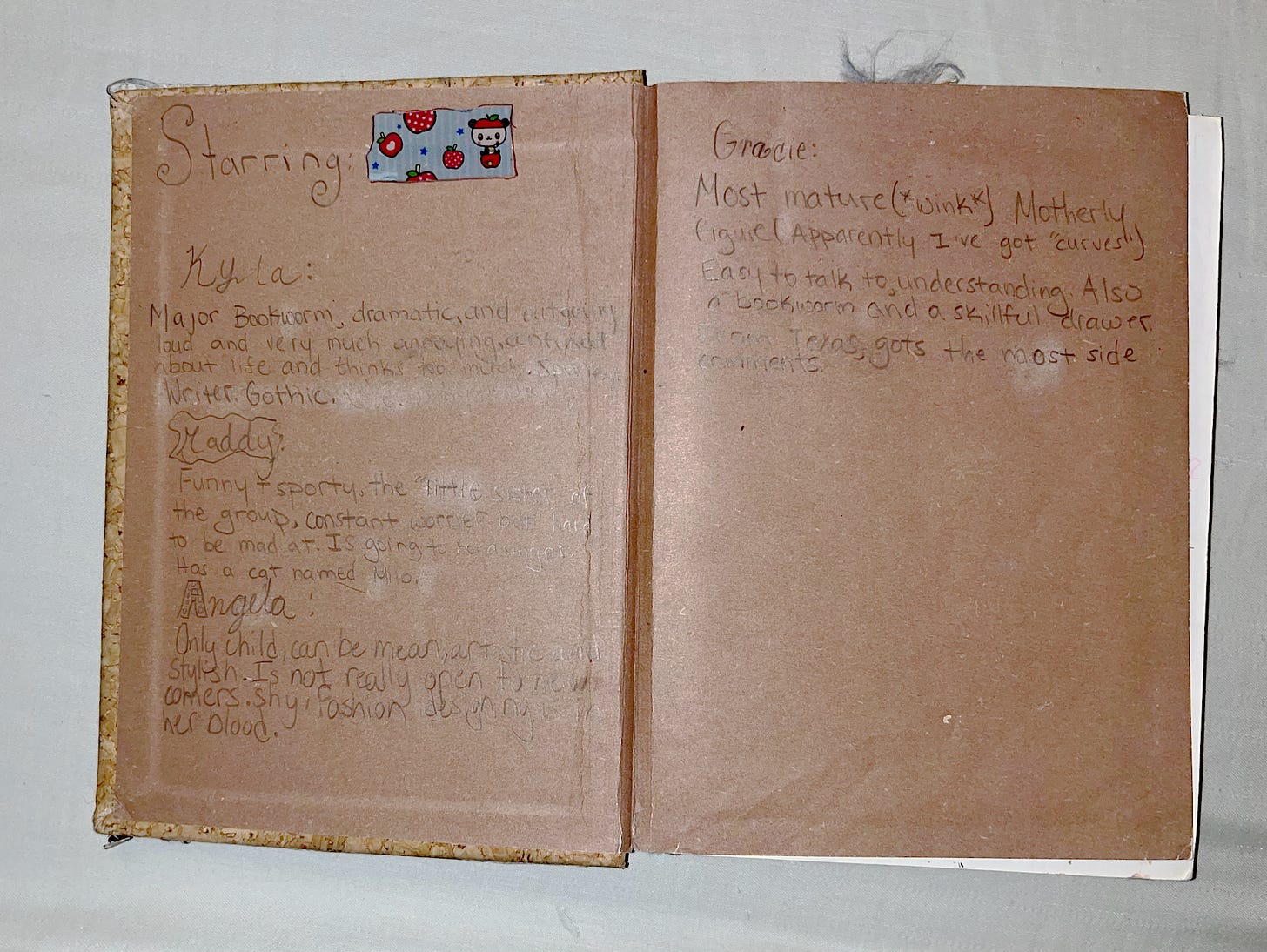

The rules of The Book were as follows:

Each person had one week to do anything they wanted to in The Book

At the end of their time, they had to pass it on to the next person in the rotation

Only people in the rotation were allowed access to the contents of the book.

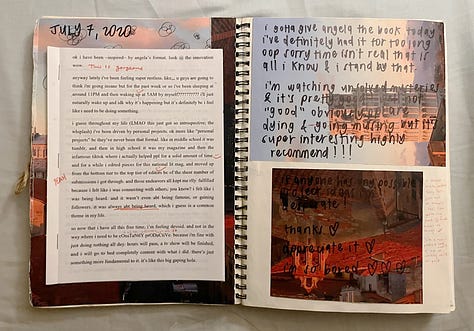

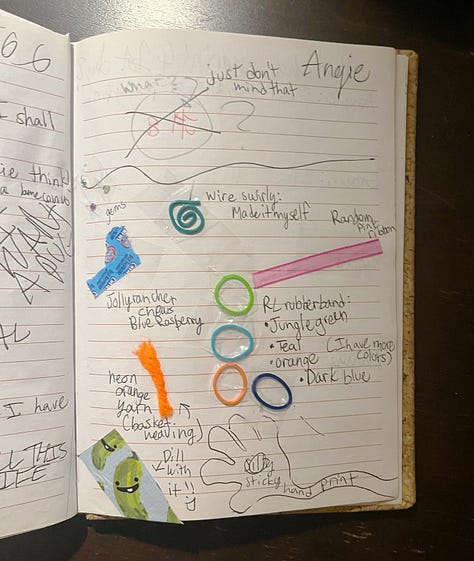

For almost a year, we passed The Book around, writing and drawing and sticking into it whatever we felt like adding. In the same sentimental, girlish way, we were replicating the model set up by the girls in The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, who shared one pair of jeans amongst themselves (despite being totally oblivious to that reference). Looking back, there was definitely a sense of exclusivity and drama in the way we went about The Book—kids are mean and we were no exception. There was no shortage of spiteful exchanges and offhand comments, many of which were fueled by a petty grudge I held against one girl who had joined later.

Aside from the drama, though, we had plenty of silly fun. The Book was a corner that we kept just for ourselves, away from the authorities and routines that usually governed our lives. It afforded us a kind of freedom and feeling of legitimacy that was still unfamiliar to us at the time. It was effectively my first journal.

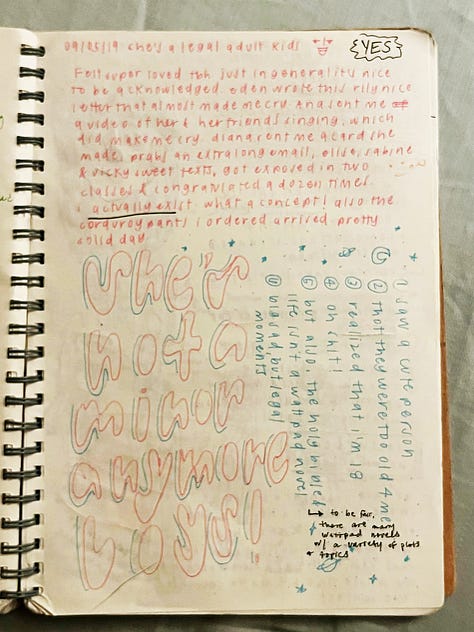

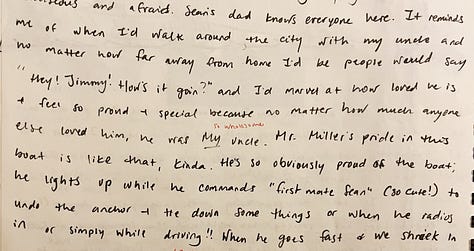

As kids do, we eventually grew bored and traded our pens and paper for shinier distractions like Fruit Ninja and Instagram. Naturally, these diversions failed to meaningfully replace the kind of freeform play and genuine connection The Book fostered. We ended up restarting it a couple of years later in late middle school, then worked on it in fits and starts until our freshman year of college. At this point, our writing had evolved into more fully formed ideas and feelings. We would trade gossip and playlists, complain about things like wisdom teeth, and reflect upon big personal things like family. From the quotidian to the existential, there was room for it all in The Book. Our rotation of people had also undergone several iterations over the years as we weathered the tenuous and shifting social dynamics of middle and high school. Ultimately, it had dwindled to just three of us: me, Kyla, and Gracie.

Over time, The Book came to mirror the progression of our friendship. Periods of distance and disconnection compelled me to reflect upon what it meant to share such intimacy and vulnerability with people I didn’t speak to for weeks on end. Sometimes it even felt like a crutch upon which our friendship leaned. But the end of our freshman years found us growing in better places into better people and we met each other where we were. Really, it was like we were befriending each other all over again, except our shared history made it feel simultaneously easier and harder to do. Throughout all this, we never thought to resuscitate our little project, maybe because we thought we’d grown out of a need to connect in that way. We had busy, multifaceted lives to attend to.

I had pretty much accepted that The Book as a practice had been lost to time, when, over winter break, Kyla and I somehow found ourselves leafing through volume after volume of the Books we’d created. It was an insane memory trip and a cathartic moment for us both. We took turns reading each other’s entries out loud until we collapsed on the floor laughing and gasping for air (this is not hyperbolic). We reminisced about the summers we had spent biking to each other’s houses, getting Rita’s Italian Ice, and playing in Northland Park. We lamented the fact that my parents were moving out of the home in which we had grown up. Although they were only moving to a town only half an hour away, it was nevertheless a very big and dramatic development to us, unofficially marking the end of our childhood.

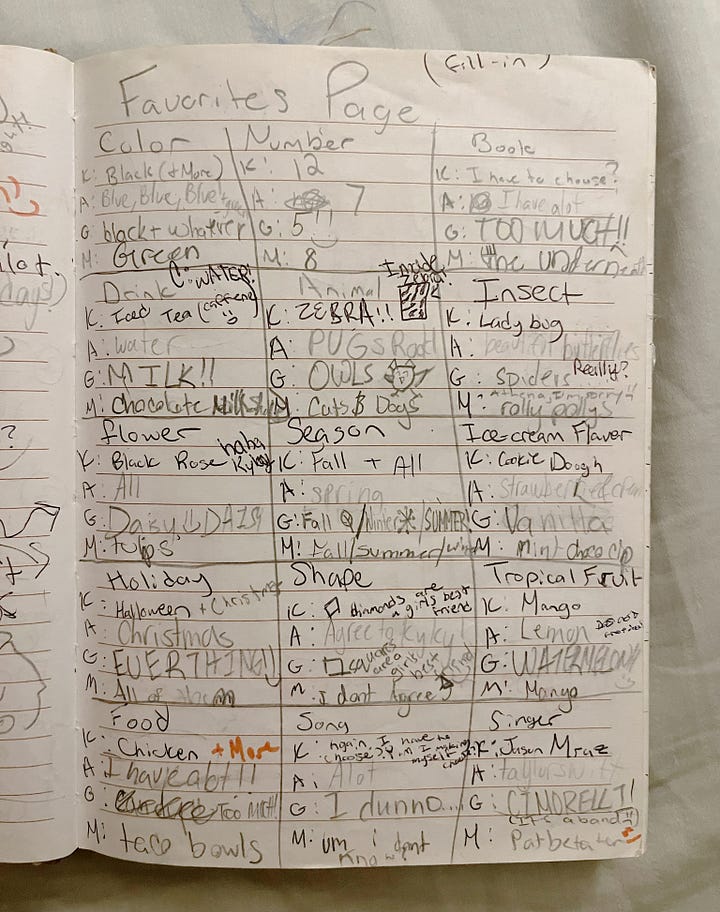

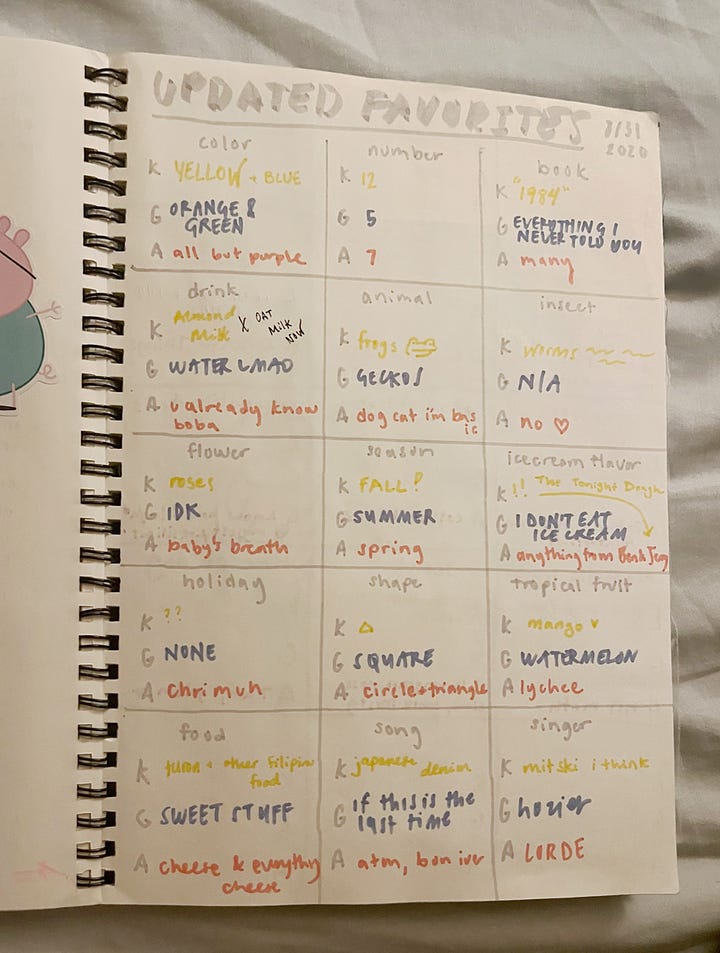

Revisiting The Book, it was remarkable to see how similar we were to these past selves. We all love to talk about how different we’ve become or how much we’ve changed in the micro-time—I was so different this time last year! Four years of college changed me!—but reading our interactions stretching all the way back to fifth grade confirmed just how consistent our personalities have been through all these seasons of life.

It was such a privilege that we could, just by reopening these Books, access a precious knowledge of who we were when we were younger. I recently came across an interview with poet Jack Gilbert in The Paris Review in which he reflects on the overwhelming richness of life. “I don’t know why [we’re] not more greedy for what’s inside [us],” he muses. “The heart has the ability to experience so much—and we don’t have much time.” Our minds and our hearts can be opaque places, Gilbert reminds us, and if we don’t try to feel what’s inside, we deprive ourselves, we lose out. Through this, he also implies that what’s inside of us needs to be somehow retrieved, that we don’t already have it. I see what he’s getting at. As much as I recognize myself through the pages of The Book, I don’t really know who I was at 10 years old—or 15 years old, or even 21 years old, really. But there is a desire to know, and that desire is what motivates a lot of us to invoke these past lives. This may be through looking at old photos going through the old knick-knacks stored in our basements or examining any other archive of our past. For me, The Book facilitated the recollection of large parts of my youth that had totally left my mind.

Revisiting these things helps us remember, which is an essential yet increasingly rare ability to sustain—especially as short-form content and its consequent disengagement continue to erode our inner worlds. When I look back on my high school and even my college years, I don’t remember much more than the broad strokes of each semester. At the time, it felt like not many things in my day-to-day life were even worth remembering, and while the things I spent my time doing were necessary, I ultimately saw them as trivial. It’s only when I look back at The Book and the things I entrusted it with that I can remember and recognize the important details among all the noise. Part of this discernment is because analog journaling forces us to slow down. As we write, it demands that we reflect. Journaling not only memorializes time, but expands it. We encounter a kind of defamiliarization of our lives when we force ourselves to deeply engage with what happened in all the days that otherwise just seemed to pass.1 Only then can we fully take in the richness of what life has offered—and continues to offer—us.

Objects like The Book not only trigger memories, but also validate a personal narrative. They are proof that, yes, this did in fact happen and I was there for it and these are the experiences that make me. They bear witness to many transitions, big and small, and the many emotions that accompany those transitions. The ability to draw a line connecting the experiences in these mementos with my own memory of them, or at least to recognize myself in them, is very comforting. This recognition is why reading the little bios we wrote for each other is so striking: we can still recognize in them the core parts of who we are today.

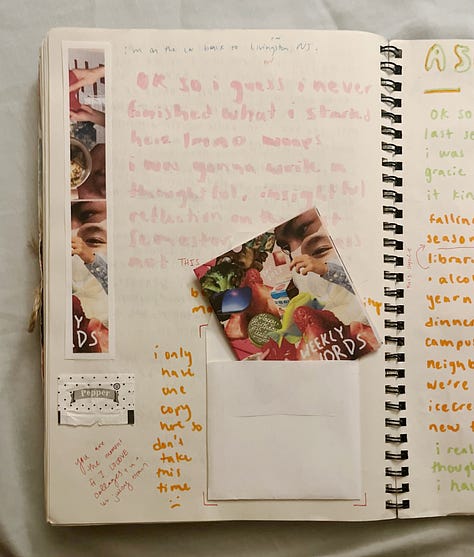

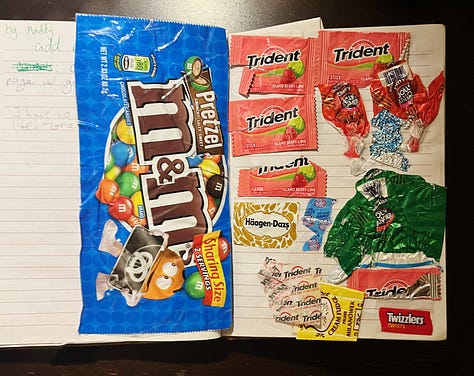

Interspersed throughout The Book is plenty of everyday life-debris—receipts, labels, dried leaves, candy wrappers. Saving these random scraps was a spontaneous and unstudied gesture, but it’s one I find myself continuously repeating. There’s a #realness and #beauty in this haphazardness that I just can’t replicate in any kind of digital space, even with all the random screenshots and digital junk that I accumulate. The physical book also promises ephemerality, which feels like a form of permission; I can write my secrets and make my weird ugly drawings and they may never move beyond the page (or the recycling bin).

The irony is not lost on me that as I preach about analog forms of writing and documentation, I’m on my laptop typing out my thoughts for our online Substack. Aside from the digital nature of our publication, though, by:association really reminds me of what Gracie, Kyla, and I created with our very own little Sisterhood-of-the-Traveling-Pants-esque project. After all, we’re just another rotation of friends sharing our thoughts and documenting our evolving ideas. As I’ve said to Sheena and Anneke, it is so beautiful and rare to share such a long, mutual commitment not only to a creative endeavor, but also to each other! Perhaps this Substack will grow to be another archive documenting and describing our nascent, twenty-something-year-old thoughts…

At the core of my interest in archive and memory is a tendency toward nostalgia and a desire to make sense of it all. I'm always searching for meaning in the details and in between the contours of a life. Things like passed-down clothing and junk drawer paraphernalia have such poignance and poetry to them, and a lot of my art practice is an attempt to unlock that by engaging with them. That’s a large part of why I wanted to revisit The Book.

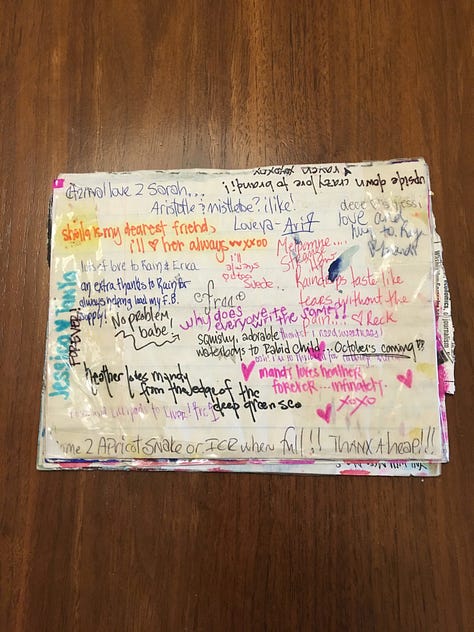

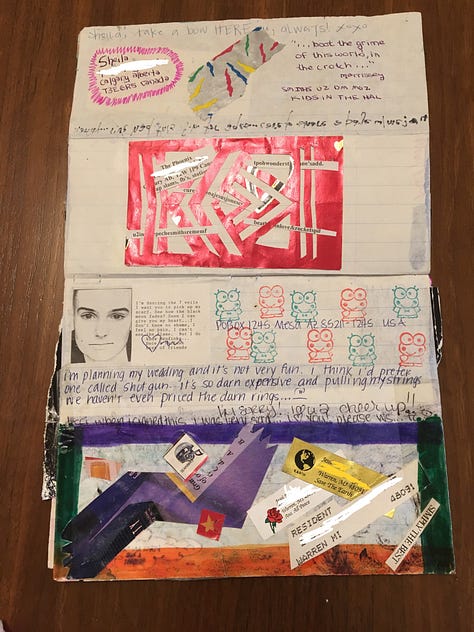

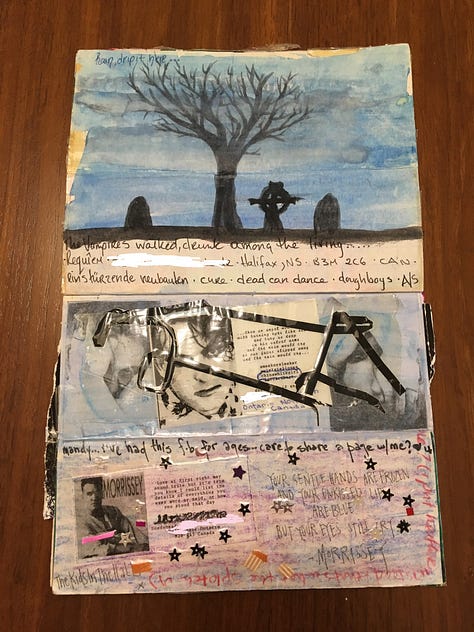

Funnily enough, soon after Kyla and I did just that, I came across an entire archive of books that were uncannily similar to ours in my Ephemeral Archive class. These “friendship books” (FBs) were largely created by youth from the punk scene in the 80s-90s. Artist and historian Leah DeVun writes about her collection of them in Public Collectors:

“FBs were collaborative books where each contributor decorated a blank page, usually with ball-point pen or water-color, but also with glitter, lace, candle wax, tin foil, ribbons, candy wrappers, whatever was on hand… Once you decorated your own page, you sent it through the mail to the next contributor. The person who filled in the last empty page was supposed to return it to the originator, whose name was on the front. At that point, a nifty piece of collective art arrived in the mail, introducing a whole new group of potential friends to each other along the way.”

It was in this same spirit that we created The Book, whether we knew it at the time or not. And it really touched me to see how people forged connections through things like FBs and chain snail mail and all the other precedents of The Book. I like to think of these projects as a kind of pseudo-third space, an accessible community gathering place separate from home and work. Neither The Book or this Substack are actual physical spaces, but they cultivate a real—albeit small—community independent of the slimy, profit-driven platforms dominating the Internet. While those platforms create cultures that force creators to mold their work to its format and algorithm, we ask how we can push, appropriate, and transform the structure for our creative ends when we use alternative means of sharing.2

A few weeks ago, I took my first trip to the campus post office since freshman year. The place looked exactly as I remembered it. I paid six dollars and thirty-four cents for the shipping and the labels (because I forgot to make them beforehand) and handed the lady a package that held a fresh notebook. In it, I had written: “Big things are happening. The Book is BACK and BETTER than EVER.”

- Ang <3

HUGE THANK YOU TO KYLA for taking care of the Books for all these years and for sending me these photos last minute. You’re the best.

Although, recent developments are starting to make me think Substack is evolving out of an alternative means and into the former…

Thoroughly joyful and interesting read, my friend. What a nice look into your little, past self and a much needed reminder to keep looking inwards (and backwards) :p